Exploring Our Habitat Improvement: Eagle Creek

History and Lessons Learned over Twenty Years of Habitat Work

Author: Dan Callahan

Among metro trout streams, Eagle Creek in Savage, MN is not a great place to fish.

It is, in fact, a short, shrubby stream, running behind industrial buildings and swinging between suburban backyards before entwining its two branches into a main stem that runs under a freeway, through the swampy Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge and into the Minnesota River. You can reach this last stretch only by wading through a very long, dark box culvert or parking your car and walking more than two miles along the railroad tracks.

While everything I described above is true, let me explain why this is my favorite place. To be clear, it is not my favorite place to fish. It is my favorite place.

While everything I described above is true, let me explain why this is my favorite place. To be clear, it is not my favorite place to fish. It is my favorite place.

In 1993, Eagle Creek’s hidden jewels included the last unstocked, wild brown trout in the Minnesota River Valley. They were threatened by urban development.

Eagle Creek is a spring creek, consisting almost entirely of groundwater, beginning on the west branch at Nathan Springs at the base of the bluff. The east branch begins below the ironically-named Trout Run Preserve housing development. The DNR had to take enforcement action during construction, when silt fences failed, allowing dirt to wash into the headwater springs.

Springs feed Eagle Creek along its whole length. Hattenberger’s Boiling Springs is the largest, a 1930’s tourist attraction with its own line of postcards. It’s also an Native American sacred site, so you won’t find a sign pointing you to it. Also, it’s not really boiling. The groundwater is 49 degrees year around, keeping Eagle Creek open even in subzero weather. The “boiling” action comes from three large, deep bedrock holes in a spring pond, which periodically erupt through the sand and clay. Johnston’s Boiling Spring is also unmarked and well camouflaged, right in the center of the stream. Most of the creek has a sandy bottom, and this ankle-deep stretch is unremarkable. Until your next step leaves you sinking in water up to your waist, or deeper. Tests have encountered no resistance even 20 feet down this spring hole!

Yet none of these natural features are Eagle Creek’s greatest asset. Its greatest value comes what we have learned from the mistakes made here. Mistakes that arguably made this one of the most important trout streams in the state during the last years of the 20th Century, and important to Minnesota Trout Unlimited’s continued success in this century.

Historically, two farms cradled the west and east branches of Eagle Creek. They were homesteaded in the 1850s, and the original families still owned them in the 1990s. Then the city of Savage moved forward with plans to run urban sewer and water services near the farms, drastically increasing their potential land value. In turn, the city put thousands of dollars in tax assessments on the farmers to pay for the sewer and water they didn’t want. This is not uncommon; it’s just the way urban expansion works. With no logical way to pay hefty assessments and keep farming, the west branch family sold their land to a housing developer.

The city of Savage took this opportunity to work with the developer on a concept plan for most of the watershed, envisioning intense urban development on both branches, including 500 homes, and on the east branch, an industrial park. The problem was that the elderly widow on the east branch didn’t want to pay her assessments by selling her farm to the city for an industrial park. She wanted to sell her land to the DNR for a bona-fide park.

After giving preliminary plat approval for the west branch housing development, the city decided no environmental review was needed. Trout Unlimited volunteers dropped their jaws, dropped their fishing poles, and picked up their pens.

TU quickly led an appeal with the state, just days before Savage was to give final approval to the platted development. The state agreed with us: An environmental review was required. They halted development. And so it began. Many TU volunteers, like TCTU chapter president Elliot Olson, didn’t have time to fish for two solid years.

Fast forward through the legal wrangling, the angry mayor throwing people out of public hearings, the volumes of information that had been missed in the initial environmental review, and jump to us losing. The development would go forward as planned, with a few tweaks based on the environmental study, which was undertaken by the City of Savage, which approved its own work. No other agency disputed the adequacy of the review.

We asked the developer to wait, to see if we could work out a way to still purchase enough land to save the stream. Every study done on Midwestern streams showed trout would not survive if the watershed was covered with that much pavement, rooftops and other impervious surfaces. The developer waited.

In 1995, Republican State Senator Terry Johnston of Prior Lake succeeded in getting bonding money for the DNR to buy land to save the stream, and establish Minnesota’s first state Aquatic Management Area (AMA). The compromise meant protecting only a 200 foot wide corridor on each side of the stream. Would it be enough to save the trout?

All around there was agreement that mistakes had been made in not identifying and valuing the few trout streams remaining where most of the state’s population lived. Immediately the DNR began a review of metro trout stream resources. That led to getting out in front of urban development to protect the Vermillion River. It also led to the establishment of many more state Aquatic Management Areas.

Perhaps lesser known is the role Eagle Creek played in Minnesota Trout Un- limited’s collaboration with the DNR over the past 20 years. In 1995 at the state capitol, two powerful DFL state senators reached across the aisle and joined Terry Johnston to save Eagle Creek. Senator Gene Merriam was head of the Senate Environment Committee, and Steve Morse was head of Environmental Finance. They toured Eagle Creek with Terry and the TU volunteers, and saw what an amazing resource was at risk.

Perhaps lesser known is the role Eagle Creek played in Minnesota Trout Un- limited’s collaboration with the DNR over the past 20 years. In 1995 at the state capitol, two powerful DFL state senators reached across the aisle and joined Terry Johnston to save Eagle Creek. Senator Gene Merriam was head of the Senate Environment Committee, and Steve Morse was head of Environmental Finance. They toured Eagle Creek with Terry and the TU volunteers, and saw what an amazing resource was at risk.

Years later, Gene Merriam was appointed as head of the DNR. Later Steve Morse was appointed head of the DNR. Both reinforced the collaboration TU and the DNR had forged at Eagle Creek. TU has a solid reputation as a levelheaded conservation organization with a statewide reach, whose several thousand members rely on science to make their case for the protection of our coldwater fisheries.

Fishing Eagle Creek

Twenty years later we know our experiment worked. The big brown trout pictured in this article were found during the DNR’s stream survey of Eagle Creek in the fall of 2014. They are living proof the stream is continuing to survive, thanks in part to special regulations.

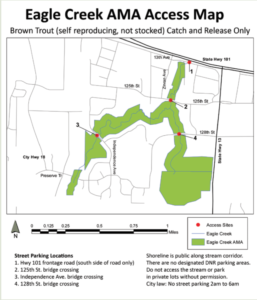

The best way to sh Eagle Creek is to take Highway 13 to 126th street. As you go west, you’ll cross the bridge over the main stem. You can park on the street west of Zinran, and walk back to sh up or downstream. There are no large fish upstream of the junction of the two branches. You also can drive down Zinran Avenue and go east on the frontage road. A small parking area borders the stream. The best fishing is from the culvert upstream to the 126th Street bridge. Though extremely brushy with challenging casting, even one nice fish can make your trip.

If you visit the stream, take the time to explore and and Johnston’s Boiling Spring. It is located on the west branch upstream of the Town and Country Campground. Park on the 125th Street by Cavelle Avenue, and walk straight south to the mowed path that leads to a pretty foot bridge. Walk upstream until you find a sharp bend, Callahan’s Corner. The spring is just upstream. Hattenberger’s Boiling Spring is further upstream on the west branch of Eagle Creek.

Interested in seeing more? Find videos online at the TCTU Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/ UCT4oDGAhijkezBWdsOW6n2g